Publications

Multi-Level Leadership Development Using Co-Constructed Spaces with Schools: A Ten-Year Journey

Authors

Howard Youngs 1, 2, * and Maggie Ogram 3

1 Bethlehem Tertiary Institute, Tauranga 3143, New Zealand

2 School of Education, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

3 Osprey Consulting, Auckland 1010, New Zealand

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Abstract

Leadership in both theory and practice usually emphasizes a person and a position. There has been a shift from emphasizing the senior level of organizational roles, to include the middle level and other sources of leadership. Nomenclature has emerged over time to reflect this, for example, collective, distributed, shared, and collaborative leadership. Another understanding of leadership needs to be added, one that does not first emphasize a person or position, instead incorporating process and practices, weaving through all levels and sources of leadership. This additional understanding has implications for how leadership development is constructed and facilitated. Over the last ten years, the authors have journeyed with groups of schools, using an emerging co-constructed approach to leadership development. The journey is relayed across three seasons. The first is the grounding of collaborative practices through inquiry, informed by a two-phase research project. The second focuses on adaptation and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas the third delves deeper into what sits behind prevalent practices that may enable and hinder student achievement. Our narrative over time shows that leadership development can be shaped through a continual cycle of review, reflection, and co-construction, leading to conditions for transformation across multiple levels and sources of leadership.

Keywords

leadership development; professional development; school leadership; collaboration; inquiry; co-construction; emergence; practices; dialogue; organizational learning

The expectation and the reality: Issues of sustainability and the challenges for primary principals in leading learning

Authors

Maggie Ogram and Howard Youngs

Osprey Consulting, New Zealand and Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand

Published

Ogram, M., & Youngs, H. (2014). The expectation and the reality: Issues of sustainability and the challenges for primary principals in leading learning. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 29 (1), 17-27.

Abstract

This article scrutinises what is expected of primary principals in New Zealand as leaders of learning, who sets these expectations and why principals are challenged with these expectations. We also consider what support principals may require to overcome the challenges that possibly inhibit their leading of learning. The findings of this small-scale qualitative study draw on two modes of data collection, document analysis and interviews with eight primary principals. For the document analysis, relevant national documents as well as principal job descriptions were studied. There was alignment between the documents, recent research literature and the interviews in relation to what is expected of principals. The findings suggest that due to principal workload and the dual school management and educational leadership aspect of their role primary principals believe that they do not devote as much time as they would wish to the specific facet of leading learning. There is also, some uncertainty and confusion related to the principals’ understanding of the term ‘leading learning’.

Keywords

Principals; educational leadership; leading learning; sustainability; workload

Introduction

The role of a primary school principal is diverse and complex. The principal is required to be the professional leader of the school and as such is required to lead teaching and learning. Prominence is given to the term ‘educational leadership’ at a time when the focus of educational leadership research and practice is the impact leadership has on improving student outcomes, indirectly and directly (Gunter, 2004; Robinson, Hohepa, & Lloyd, 2009; Strain, 2009). The linkage, however, between school leadership and improving student outcomes, according to Cardno (2012, p. 18) “remains untested except in a few studies” (for examples, see Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom and Anderson [2010] and the New Zealand Ministry of Education’s School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Best Evidence Synthesis (BES) by Robinson et al. [2009]). Despite the attention given to leadership and student outcomes, there is still the challenge of how the chief executive role of principals in decentralised education systems incorporates the leading of learning while also being responsible for financial, property, human resource and strategic management (Brundrett & Rhodes, 2011). This challenge is a poignant one for principals in New Zealand schools who operate under a highly devolved self-managing school system that is among the most devolved across OECD countries (Pont, Figueroa, Zapata, & Fraccola, 2013).

This article is research-based and was prompted by a keen interest to understand why principals in primary schools are challenged with the expectation that they lead teaching and learning. While much is written about principals, and they may have lots to say, they may not go on the public record in a formal article (Gunter, 2012). This too was a motivation behind this article, which argues that principal sustainability is still an issue that is not yet resolved. We initially provide an overview of the literature base relevant to this research, followed by a review of official and school-based documents that illustrate the role expectations of New Zealand primary principals. This provides a backdrop for interviews with eight New Zealand primary school principals in relation to their understood expectations of their role as educational leaders and the challenges they face to meet those expectations. The main findings of the research study are discussed with implications and concluded with our argument that principals alone cannot address the issues raised in this article.

Expectations of principals

Educational leadership focuses on the leadership contribution a principal and staff make to improve teaching and learning. There has been a significant shift in the nomenclature away from ‘educational management’ to ‘educational leadership’ since the end of the 1990s, a decade synonymous with managing educational organisations. Robinson (2004) aptly captured this shift ten years ago:

The new focus on the leadership and improvement of teaching and learning sets a very ambitious agenda for school leaders and for those who prepare and develop them. The leadership goal is no longer to develop a vision, build a good school-community relationship, or manage the school or department efficiently. The new goal requires leaders to do all those things in a manner that improves teaching and learning. (p. 40)

In parallel to this has been an increased emphasis on having leaders at many levels due to the additional responsibilities that principals in general have picked up since the start of the 1990s (O’Donoghue & Clarke, 2010). Consequently, principals are expected to recruit and train teachers into this greater distribution of delegated leadership work, all the while without lessening their own influence in decision-making processes (Louis et al., 2010; Waterhouse & Møller, 2009).

Despite the emphasis on principals and other leaders working with staff to improve student achievement, the role of principal is still critical to schools. This role traverses instructional leadership, influencing the working conditions of staff, fulfilling external requirements associated with ensuring their school meets expectations set by governing bodies, as well as the likelihood of teaching for those in small schools. Research studies continually affirm the multiplicity of expectations. The meta-analysis of school leadership research that informed the School Leadership BES (Robinson et al., 2009) showed how, in high-achieving schools, teachers viewed their principal as a key source of instructional advice. In these high-achieving schools, principals were also more likely to discuss with teachers how their instruction affected student achievement. However, according to MacBeath (2009) this expectation can also have a potential down-side, particularly in England: when student achievement does not improve the principal can also be viewed as ‘failing’. Despite this direct association between student achievement and principals, their influence on student achievement is often mediated through the teachers they lead.

Principals are viewed as having a direct influence on teachers’ motivation and working conditions which then has a flow-on effect to student achievement, an association that is evident in large quantitative research studies (for example, see DuFour & Marzano, 2011; Louis et al., 2010). Another meta-analysis from the Ministry of Education BES series, Teacher Professional Learning and Development (Timperley, Wilson, Barrar, & Fung, 2007), revealed that principals play a key capacity building role “within a school by developing the intellectual and professional capital of its staff” (p. 193). This is a key theme evident in educational leadership research (for example see, Blase & Kirby, 2009; Robinson et al., 2009) and highlights the influence principals can have with teacher development and growth.

Principals are also agents of their employers and usually public servants “appointed as a managerial job holder” (Gronn, 2003, p. 17). The shift to self-managed schools over the last two decades has not only meant more espoused local control, but also a higher level of accountability to school boards, and district and national government agencies. Principals “have a duty to advise and assist the governing body in discharging its functions” (Brundrett & Rhodes, 2011, p. 25), an activity confirmed in a New Zealand-based national study where data was collected from school board chairpersons and principals (Youngs, Cardno, Smith, & France, 2007). As a consequence of the management-governance space that principals navigate, they are inevitably positioned as CEOs of their organisations, particularly in highly devolved school systems.

Within the multiplicity of these expectations, principals in New Zealand would like to spend more time actively as pedagogical and curriculum leaders in their schools, leading with others the continual development of teaching and learning (Cardno & Collett, 2004; Hodgen & Wylie, 2005; Wylie, 2012). This leads to the possibility of an inherent tension related to the multiple aspects of the principal’s role, particularly with the increased emphasis and expectation of the principal to primarily lead learning. This is a tension that is unlikely to go away while New Zealand schools operate under the self-managing school system that is currently in place (Wylie, 2012).

Challenges surrounding the expectation of the principal’s role as an educational leader

The role of principalship is challenging and complex. Gronn (2003) suggests that schools are a good example of an organisation that operates through distributed leadership, through, for example, curriculum leaders or the senior management team. Despite the practise of distributed leadership, the principal is seen as responsible for every aspect of the operational running of the school in a self-managed system. This is a key issue in the challenge for principals in leading learning. The principal is expected to be ‘all things to everyone’. The challenge this brings to the role of principalship is evident in the literature (Bottery, 2004; Brooking, Collins, Court, & O’Neill, 2003; Cardno & Collett, 2004; Williams, 2003; Wylie, 2012). Brooking et al. (2003) comment on the changing and growing role of principalship in New Zealand since 1989 and the introduction of self-managed schools. Wylie (2012) argues that this presents a tension to principals when time given to administrative tasks lessens their time to have impact with teaching and learning. The commonly held view in the literature is that self- management has brought a greater workload (Bennett, 1994; Cardno & Collett, 2004; Fullan, 2008; Hodgen & Wylie, 2005; Wylie, 2012). A central role of the principal is to lead learning and to be ultimately accountable for the improvement of student outcomes in the school. However, there is also agreed recognition that the principal’s role carries a considerable and diverse workload in New Zealand schools (Hodgen & Wylie, 2005). There is a dilemma surrounding how the principal meets the requirements of being the chief executive officer of the school and also gives priority to leading learning.

The principal’s workload and the multi-dimensional aspects of the principal’s role are highlighted in the findings of a report to the New Zealand Principals’ Federation researched and written by Hodgen and Wylie (2005). Under the auspices of the New Zealand Council for Educational Research, the report offers pertinent data relating to the issues surrounding principals leading learning. Their study suggests that workload issues are not simply the long hours worked, but rather the multi-dimensional aspects of the principal’s role. Wylie (2012) also notes that this situation was unchanged when relevant data were collected in 2010. This shows that principal sustainability is an ongoing issue in New Zealand’s devolved education system despite the advent and popularisation of distributed leadership to and through other staff (Youngs, 2009). The literature shows the association of increased principal workload with principal stress and well-being. These are apparent at the same time as the emphasis is increasingly placed on the principal’s role being primarily one of educational leader. In the context of the Ministry of Education (MoE) in New Zealand, there once existed a professional leadership plan referred to as a Professional Leadership Strategy (PLS), the starting point for which was the Kiwi Leadership for Principals model (MoE, 2008). It was intended that the strategy would provide a plan intended to strengthen and support leadership in New Zealand schools. One of the challenges that the plan was expected to address was in response to the research findings of Hodgen and Wylie (2005) who suggested that the many demands of leadership and administration can be a source of tension for the principal when deciding how to prioritise time and attention. As part of the PLS, a support programme for experienced principals was piloted with a great deal of success (Cardno & Youngs, 2013). Unfortunately, due to restructuring and the loss of key people at the Ministry of Education this programme has not continued (Wylie, 2012); leaving the issue of addressing the tensions principals face somewhat in limbo at the time this article was written.

The challenge to principals would seem to be heightened by the issue of accountability (MacBeath, 2009; Odhiambo, 2007; Wiseman, 2005). In the New Zealand context, Piggot-Irvine and Cardno (2005) state: “The principal is accountable to the Board of Trustees as the chief executive of the board, and is responsible for the professional leadership of the school” (p. 85). The school community and the wider community see the principal as accountable for student performance and attainment. Through research in Australia, Odhiambo (2007) views that many school principals are spending considerable time on managerial responsibilities and addressing accountability requirements. This is not to suggest that these tasks are unimportant but the issue is again raised about time to complete these tasks possibly taking priority away from the principal leading learning. Principals, it may be argued, need to have the kinds of educational leadership skills that enable them to reflect critically, helping them to maintain the optimum conditions for teaching and learning and to build community confidence in the school while attending to accountability requirements. The views of the principals in our research question whether this is actually possible.

The aim of the research

The purpose of the research project was to scrutinise the expectations and the reality surrounding the challenges for principals leading learning in New Zealand primary schools with rolls of between 300–600 students. The age range of the students in the school was 5–11 years. An aim of the study was to understand what is expected of principals as educational leaders and who set these expectations. The research investigated why principals in middle-sized primary schools are challenged with the expectation that they lead learning. Additionally, the study sought to explore how principals could be supported to overcome the challenges inherent in the expectation that they should effectively lead learning. The study was informed through three research questions:

- What is expected of principals as educational leaders and who sets the expectations?

- Why are principals challenged with the expectation that they lead learning?

- How could principals be supported to overcome the challenges inherent in the expectation that they

should effectively lead teaching and learning?

Methodology

The qualitative study used two approaches to gathering data. The initial method of documentary research was used to analyse documents related to principals in the New Zealand education system. Specifically, these were:

- National Education Guidelines (NEGs), The National Administration Guidelines (NAGs), and The Professional Standards for Primary Principals (MoE, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c);

- the Kiwi Leadership for Principals model (KLP; MoE, 2008);

- examples of job descriptions of principals participating in the interviews; and,

- Process Indicators used by the Education Review Office (ERO, 2011).

The data from these documents established a platform for the research surrounding why primary principals are challenged with the expectation that they lead learning, provided a frame of reference and supported the main research method of individual interviews. Eight principals were individually interviewed. The number of years’ experience that each principals had in the principal’s role varied. This extended from one principal’s twenty nine years’ experience, beginning before the introduction of the devolved self-managing school reforms, through to one principal who was in her second year of principalship. All but one had been a principal for at least four years. The findings presented in this article suggest that the relationship and dynamics between the documented expectations placed on principals in leading learning and the interviewed principals’ perceptions of that reality point to a degree of unsustainability of the role in its current form.

Main findings

The expectations of principals as leaders of learning as found in the documentation

Through analysis of NAG 1, it is evident that the ministerial expectation is that the Board, through the principal, will ensure the development of teaching and learning programmes. It is also expected that learning will be led by the principal and students’ progress and achievement will be realised through effective assessment practices. Additionally, that teaching and learning strategies will be developed and implemented to meet the needs of individual students as assessed, in order to ensure positive student outcomes. The implication is that the principal is expected to be a leader of learning in ensuring that the school meets the requirements of NAG 1.

In NAG 2 the stated expectation of the principal is that, as school leader, he or she working with the Board and staff will lead strategic planning that provides effective professional development that results in successful student outcomes. NAG 2a makes the further requirement that the principal, along with the teaching staff and Board, will report to students and parents regarding educational achievement against the National Standards at least twice a year. The principal and Board are also legislatively required to report on students’ achievement against the National Standards in the school’s Annual Report submitted to the Secretary for Education. The expectation that the principal will develop and maintain schools as learning organisations and improve outcomes for all students is also evident in the KLP (MoE, 2008) model. In alignment with NAG 2 there is the expectation within the KLP model that the principal will ensure that staff receive professional development and that others are developed as leaders. The underlying purpose in the KLP model for these strategies is to enhance learning and teaching in order to improve learning experiences and outcomes for all students. The aspects of culture, pedagogy, systems, partnerships and networks that are fundamental to the KLP model form the four Areas of Practice of the Professional Standards for Primary Principals. Each of these four areas is explicitly linked to the expectation of enhancing student learning.

The same expectation of the principal as a leader of learning was seen in an example of a principal’s job description provided by one of the participating principals. A stated expectation was to lead strategic planning that provided leadership for curriculum implementation and development. The principal was expected to be responsible for the development of effective school-wide assessment procedures that enhanced teaching and learning. There was also the clear expectation to oversee staff professional learning programmes and ensure that all staff members were part of a school-wide appraisal system that positively impacted on student outcomes. The expectation that the principal should lead curriculum management and manage staff performance was also clearly documented in the job descriptions of the other participating principals.

The document from the Education Review Office, specifically through the Professional Leadership Indicator, showed agreement with all of the documents discussed. Here, it was shown that the Education Review Officers, on visiting schools, would be looking for evidence that the principal’s professional leadership of strategic curriculum planning informed by assessment data was expected to lead to improved teaching and learning. There was also the expectation in this Indicator that the school Board would provide access to well-targeted professional development that met the needs of the school as a whole and the needs of those in leadership roles. This would be ensured through the principal.

Selected themes from the individual interviews in relation to the expectations and the challenges presented to principals

A key theme evident from the interview data using the words of one of the principals was “the magnitude of the job”. Another principal described how they were appraised over 26 areas of responsibility. There was a sense that a principal was “responsible for everything to everyone”, while trying to be “all things to all people”. Despite this, one of the principals epitomised the view of the others, stating how it was their own decision to make sure they were a “leader of learning”, while another explained it was all about “trying to walk the talk [as a leader of learning and] to model [this to staff]”.

Another dominant theme was the importance of professional development. This can be divided into, firstly, the principals’ self-expectations for the need for their own ongoing professional development to improve their pedagogical knowledge and, secondly, the principals’ expectation that they should ensure the professional development of their staff in order to improve student outcomes. However, principals found it a challenge to keep themselves up to date in a manner so they weren’t superficially “picking up some little snippets of a course or a conference”. In relation to improving student outcomes through professional development as a means of managing change, principals described it as “going slowly, when you want to run” balancing the perceived need to keep staff happy so they wouldn’t “all be on my doorstep” while dealing with staff who did not want to change.

Within the theme of professional development was also the expectation that principals believed that they needed to ensure their schools followed a rigorous appraisal system in relation to supporting and ensuring effective professional growth. In relation to prioritising the focus on students’ learning, a significant theme was the importance of principals ensuring the collating and analysing of assessment data to understand the needs of individual students and to use this information to inform strategic planning. The most significant challenge to principals in leading learning seemed to be pressures related to a huge workload and a lack of time due to the vastness of the whole scope of the role. One found it easy to “get stuck down with the administration tasks”, while another, drawing on their experience of principal training with tongue in cheek, claimed “it’s [principalship] all about learning and teaching. Ha ha, yeah right!”.

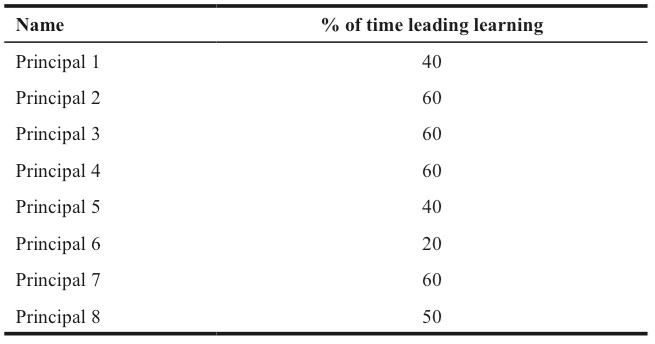

Before closing each interview, every principal was asked what percentage of their time they felt they spent leading learning. Table 1 provides the results. It is interesting that all of the principals commented that they found this the most difficult question to answer. Each of them commented that it depended on what is meant by ‘leading learning’. They all expressed dismay that they could not say that they gave leading learning a greater percentage of their time. Some consistency can be seen in half of the principals stating that they estimated that they spent 60% of their time leading learning, raising the question of whether principals can actually be leaders of learning as is expected of them and by them in the current devolved nature of New Zealand schools.

Table 1. The percentage of time that principals believe they spend leading learning

A discussion of some main findings and the implications for practice

In researching the principal’s role through documentary analysis and the perceptions of the principals given in individual interviews, we suggest that two main findings are particularly interesting. Firstly, that the principal’s dual function of focusing on leading learning and being a general manager in the current policy environment raises issues of how sustainable this is. Secondly, that the leading learning function is still surrounded by some confusion for principals.

The principal’s dual role

The expectation that the principal’s role as educational leader includes the dual functions of focusing on leading learning and also ensuring the smooth daily operational running of the school is confirmed in the documents that were analysed for this research study. The duality of the role is embedded in the National Administration Guidelines (NAGs) 1–6 in that, along with the areas of curriculum in NAG 1 and self-review in NAG 2, they also hold expectations of the principal in the areas of personnel, finance and property, health and safety, and legislation. The duality of the principal’s role in this regard is also clearly evident in the KLP model that states, “As well as being pedagogical leaders, principals are responsible for the day-to-day management of a broad range of policy and operational matters, including personnel, finance, property, health and safety, and the interpretation and delivery of the national curriculum” (MoE, 2008, p. 7). The Professional Standards for Primary Principals has been shown to closely align with the KLP model and to form the basis of all of the job descriptions of the principals interviewed in the study. In scrutinising the Professional Standards for Primary Principals, the facet of leading learning was evident throughout. However, in the Area of Practice within the Professional Standards for Primary Principals entitled ‘systems’, the expectation is for the principal to also show leadership that results in the effective day-to-day operational running of the school and effective management of finance, personnel, property and health and safety systems. Thus, the expectation of the duality of the principal’s role is highlighted in the Professional Standards for Primary Principals. The significance of this was that the principals looked to the Professional Standards, as they were seen in their view as “a stake in the sand” and outlined “what you are supposed to do”.

The responses of the principals strongly concurred with the literature (Bennett, 1994; Brooking et al., 2003; Cardno & Collett, 2004; Wylie, 2012) that the primary principal’s role is a dual role, comprising of leading learning and leading and managing the daily operational running of the school. They all saw the role as vast and that it involved being a leader of learning and a general manager. The tasks they included within these roles of being a leader of curriculum initiatives and sustaining the school vision and strategic plan and also working on areas of finance, property, legislation, and health and safety aligned with the expectations of the documents analysed for this study.

The overwhelming challenge experienced by all of the principals in this study was the vastness of their workload. As a result of the demands of the expectations of meeting the dual role of leading learning and managing the school at a daily operational level, all of the principals interviewed in this study believed that they did not give as much of their time as they felt they should to leading learning. The principals interviewed agreed that the need to complete administrative tasks allowed less time than they would desire to focus on leading learning. The challenge for principals was that as educational leaders they were expected to focus their leadership practice on leading learning to improve student outcomes yet also complete the administrative tasks of a general manager. One principal explained how they tried to meet this challenge, stating, “everything I do I have to ask if this is going to improve learning outcomes for students”. Despite the principals’ desire to lead learning, they were still beset with a considerable workload issue which is a dominant theme found in the literature (Bottery, 2004; Fullan, 2008; Hodgen & Wylie, 2005). Brooking et al.’s (2003) research suggested that an increase in workload and time taken by principals on administrative tasks at the expense of leading learning would significantly contribute to a crisis in New Zealand schools with regard to the preparation, recruitment, professional development and retention of principals.

The research of Brooking et al. (2003) showed that many first-time principals in New Zealand were leaving the job because of a perceived low level of support. A considerable amount of literature is available surrounding support initiatives specifically for principals in the leading of learning (e.g. Robinson et al., 2009). The First Time Principals Programme in New Zealand focuses on the need for principals to be helped to develop skills of reflection, self-assessment and critical thinking specifically to lead learning. However, when the principals who were interviewed as part of the research provided suggestions regarding what support they might find helpful, they focused on support that they expected to receive in performing the whole scope of their role, rather than specifically support for leading learning. We suggest that the inference may be taken that if principals received more support in the whole scope of their role and its dual functions they may be able to devote more time to focusing on leading learning, an aim which they all expressed as desirable. Coupled to this was the principals’ desire for greater support at a local networking level with other principals. Some bemoaned the drop-off in formal support beyond the First Time Principals Programme, while appreciating what support they received through having a “good admin secretary”, “conscientious deputy principals”, and a school culture that enabled open and professional dialogue about learning with staff.

The meaning of leading learning

Many different forms of terminology were found to define leading learning in the literature reviewed for this research study. Those specifically scrutinised were ‘professional leadership’, ‘educational leadership’, ‘curriculum leadership’, and ‘pedagogical leadership’. However, additional terminology was evident in the literature base for the study. Blase and Blase (2000) used the term ‘instructional leadership’, while Southworth (2004) referred to ‘learning centred leadership’. Various terms were also found to imply a focus on leadership. Those referred to for this study were ‘strategic planning’, ‘distribution of leadership’, ‘evaluating and developing staff’. There was alignment between these terms, implying a focus on leadership in the documents that were analysed. The leadership dimensions shown to have the greatest impact on student outcomes in the School Leadership BES (Robinson et al., 2009) were the principal promoting and participating in teacher learning and development and ensuring the alignment of the curriculum to school goals. The expectations of the principals interviewed in this study were similar to these key dimensions to leading learning. These key dimensions were that principals should use professional development to lead learning and be actively involved themselves in whole staff professional development, as well as their own distinct professional learning, and ensure that assessment data were used to inform strategic planning.

However, a dilemma is also evident. Interestingly, in answering the first question of the interview schedule when asked to describe the scope of their role, the principals all answered with certainty that they were ‘leaders of learning’. Yet, having progressed through the interview questions and having arrived at the final question that required the principals to consider what percentage of their time they would estimate they spent leading learning they all appeared quite uncertain and confused. Many of them commented they found it the most difficult question of the interview to answer. Without exception, each commented that it depended what was meant by ‘leading learning’. Within the vastness and duality of the principal’s role, confusion and a lack of clarity was apparent regarding which of a principal’s multiple tasks constituted ‘leading learning’. We argue that it would be helpful if greater distinction was made between ‘leading learning’ and ‘managing the conditions conducive to meeting expectations of learning’. ‘Leading learning’ indicates more of a direct relationship between leadership and learning, whereas the latter terminology suggests that meeting the expectations of learning are also mediated through managing conditions, namely through personnel, strategic, financial and site management.

Recommendations and conclusion

Through the course of this research study, the need for clarity around the term ‘leading learning’ became more apparent. A recommendation is that primary principals in New Zealand receive opportunities for professional development in order to clarify what is meant by ‘leading learning’ and how this is enacted both directly and indirectly through managing conditions. A review of this cannot be carried out independent to the issue of sustainability. The role of the principal in New Zealand’s highly devolved education system has continually and perhaps increasingly become unsustainable. Perhaps it is time, as Wylie (2012) argues, to stand back and undertake a critical system-level review of self-management.

Within the current context, the main recommendation suggested to primary principals is that they are proactive in seeking their own ongoing professional development, networking with other principals to seek greater clarity regarding their role in leading learning, and continually look for ways to filter their administrative and management tasks so that they are more likely to impact the conditions of learning. During the course of the interviews, all of the principals emphasised the importance of sustaining their own professional learning. However, while principals may over time experience some shift from a dual role to one akin to leading learning, this study and the ones that have preceded it suggest that this will be hampered until there are shifts at a system level. In the meantime, principals can be supported to some extent through effective administrative staff, their deputy principals and their own school culture, provided it is one that enables open and critical dialogue amongst staff with a focus on learning. Beyond that, it will take courage to adjust the wider environment at a system level if the ongoing issue of sustainability is to be addressed so that principals can be leaders of learning as much as they hope to be.

References

Bennett, C. (1994). The New Zealand Principal Post-Picot. Journal of Educational Administration, 32(2), 35-44.

Blase, J. & Blase, J. (2000). Effective instructional leadership: Teachers’ perspectives on how principals promote teaching and learning in schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 38(2), 130-141.

Blase, J., & Kirby, P. C. (2009). Bringing out the best in teachers: What effective principals do (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Bottery, M. (2004). The challenges of educational leadership. London: Paul Chapman.

Brooking, K. Collins, G. Court, M. & O’Neill, J. (2003). Getting below the surface of the principal recruitment ‘crisis’ in New Zealand primary schools. Australian Journal of Education, 47(2), 146-158.

Brundrett, M., & Rhodes, C. (2011). Leadership for quality and accountability in education. London: Routledge.

Cardno, C. (2012). Managing effective relationships in education. London: Sage Publications.

Cardno, C. & Collett, D. (2004). Curriculum leadership: Secondary school principals’ perspectives on this challenging role in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Educational Leadership, 19(2), 15-29.

DuFour, R., & Marzano, R. J. (2011). Leaders of learning: How district, school, and classroom leaders improve student achievement. Bloomington: Solution Tree Press.

Gronn, P. (2003). A matter of principals. Australian Journal of Education, 47(2), 115 – 117.

Gunter, H.M. (2001). Leaders and leadership in education. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Gunter, H. (2004). Labels and labelling in the field of educational leadership. Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education, 25(1), 21-41.

Hodgen, E., & Wylie, C. (2005). Stress and wellbeing among New Zealand principals. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Louis, K. S., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K., & Anderson, S. (2010). Learning from leadership: Investigating links to improved student learning (Final report of research to the Wallace Foundation). University of Minnesota, University of Toronto.

MacBeath, J. (2009). Shared accountability (principle 5). In J. MacBeath & N. Dempster (Eds.), Connecting leadership and learning (pp. 137-156). London: Routledge.

Ministry of Education. (2009). Evaluation Indicators for Education Reviews in Schools. Wellington: Ministry of Education. New Zealand. Retrieved June 18 2009 from http://ero.govt.nz

Ministry of Education. (1989). National Education Guidelines. Wellington: Ministry of Education. New Zealand. Retrieved March 5 2009 from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/education

Ministry of Education. (2008a). Principal and Teacher Performance Management. Wellington: Ministry of Education. New Zealand. Retrieved March 9 2009 from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/education

Ministry of Education. (2008b). Kiwi Leadership for Principals: Principals as Educational Leaders. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Odhiambo, G. ( 2007) Power or purpose? Some critical reflections on Future School Leadership. Leading and Managing, 13(2), 30-43.

O'Donoghue, T., & Clarke, S. (2010). Leading learning: Process, themes and issues in international contexts. London: Routledge.

Piggot-Irvine, E. & Cardno, C. (2005). Appraising Performance Productively: Integrating Accountability and Development. Auckland: Eversleigh Publishing.

Robinson, V.M.J. (2006). Putting education back into educational leadership. Leading and Managing, 12(1), 62-75.

Robinson, V.M.J. (2007). School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Identifying What Works and Why. Australian Council for Educational Leaders, (41) Winmalee: Australia.

Robinson, V.M.J.. Hohepa, M. & Lloyd, C. (2009). School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Identifying What Works and Why. Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration (BES). Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

Southworth, G. (1995). Looking into Primary Headship: A Research Based Interpretation. London :The Falmer Press.

Southworth, G. (2004). Primary school leadership in context: Leading small, medium and large sized schools. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Strain, M. (2009). Some ethical and cultural implications of the leadership 'turn' in education: On the distinction between performance and performativity. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 37(1), 67-84.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning and development: Best evidence synthesis iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Van Nieuwerburgh, C, (2012). Coaching and mentoring for educational leadership. In C. van Nieuwerburgh (Ed.), Coaching in Education (pp. 25-45). London:Karnac.

Waterhouse, J., & Møller, J. (2009). Shared leadership (principle 4). In J. MacBeath & N. Dempster (Eds.), Connecting leadership and learning (pp. 121-136). London: Routledge.

Wiseman, A.W. (2005). Principals under pressure: the growing crisis. Lanham: ScarecrowEducation

Wylie, C. (2012). Vital connections: Why we need more than self-managing schools. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

New Zealand Education Gazette Volume 93 Number 19

Article title: Looking back on a future-focused initiative

This article published in the Gazette Professional Development Supplement (October 2014) describes the establishing of the eLearning Network amongst East Auckland schools and its successes in providing ongoing professional development for teachers in relation to future-focused learning and teaching.

Keywords

Future-focused, eLearning, collaboration, teaching as inquiry, modern learning environments